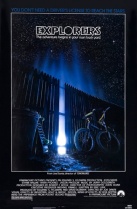

Cinefex issue #23 examines no less than three movies but, as far as the cover pictures go, the star of this particular show is Explorers, Joe Dante’s 1985 slice of family-friendly science fiction. Up front is a hero shot of the rather funky-looking spaceship operated by whimsical aliens Wak and Neek. Look closely and you’ll see a miniature Thunder Road poised to enter the big ship’s docking bay. On the back cover is a close-up of the alien Neek. The character was performed by Leslie Rickert wearing an elaborate full-body suit created by Rob Bottin. The three articles contained within this issue span 72 pages.

Cinefex issue #23 examines no less than three movies but, as far as the cover pictures go, the star of this particular show is Explorers, Joe Dante’s 1985 slice of family-friendly science fiction. Up front is a hero shot of the rather funky-looking spaceship operated by whimsical aliens Wak and Neek. Look closely and you’ll see a miniature Thunder Road poised to enter the big ship’s docking bay. On the back cover is a close-up of the alien Neek. The character was performed by Leslie Rickert wearing an elaborate full-body suit created by Rob Bottin. The three articles contained within this issue span 72 pages.

- Explorers – The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of (article by Adam Eisenberg)

- Baring the Soul of ‘Lifeforce’ (article by Glenn Campbell)

- Shooting for an ‘A’ on ‘My Science Project’ (article by Stephen Rebello)

In September 1985, the LA Times published a report mourning the passing of a summer of dismal box office returns. It puts part of the blame on ‘genre madness’, wryly labelling the disappointing season as ‘the summer of “My Real Weird Genius Science Project,” the amalgamated title of three sound-alike films released almost simultaneously by different studios.’

Explorers

Digging under the skin of that summer of misfires, this issue of Cinefex kicks off with Explorers – hardly a big hit, although it’s fondly remembered by many. Adam Eisenberg divides his attention between Rob Bottin’s outlandish aliens, ILM’s crisp miniatures and opticals and the short CG sequences delivered by Omnibus. The latter are of particular interest because, if you leaf back through the calendar, you’ll see that just a few short months after Explorers was released one of the real game-changers in digital effects hit the theatres.

That game-changer was Young Sherlock Holmes, and it was revolutionary because it featured mainstream cinema’s first fully-rendered CG character (a living stained-glass knight). The vision demonstrated by ILM’s Pixar group in bringing the knight to life stands in sharp contrast to the rather cautious approach of Dante and his team with regard to the digital dream sequences featured in Explorers.

That game-changer was Young Sherlock Holmes, and it was revolutionary because it featured mainstream cinema’s first fully-rendered CG character (a living stained-glass knight). The vision demonstrated by ILM’s Pixar group in bringing the knight to life stands in sharp contrast to the rather cautious approach of Dante and his team with regard to the digital dream sequences featured in Explorers.

Dante’s lack of confidence in the digital medium is apparent from the start. Referencing Tron and The Last Starfighter, he says that ‘after a while, the novelty of the [digital] effect begins to wear off.’ He explains how he chose CG for the Explorers dream sequences only ‘because we wanted [them] to look a little bit different,’ and confesses to a hands-off approach to their actual production. ‘I’m not as … computer-wise as other people might be,’ he concludes.

Dante’s attitude represents a view prevalent at the time: that CG was only really suitable for scenes set inside computers, video-games or dream worlds. Need spaceships? We’ll build models and shoot them under motion control. Need aliens? Let’s put some guys in suits. Digital effects? Well, maybe they’ll catch on some day.

Eisenberg’s description of the Omnibus digital facility reminds us that, back in 1985, computers were still objects of mystery. ‘Entering [the facility],’ he says, ‘is like stepping onto a movie set from Wargames or Colossus – The Forbin Project.’ He describes black-walled rooms filled with ‘a type of technology that fifteen years ago was science fiction.’ Today, the Omnibus process of creating 3D models by digitising hand-drawn blueprints just sounds quaint.

While talking about the digital effects, Eisenberg retains that slightly reverential tone familiar from earlier Cinefex articles on the subject (notably those by Peter Sørensen). When it comes to ILM’s more conventional visual effects output, he shows us a well-oiled machine working its way smoothly through familiar gears. The article runs the whole gamut from miniature landscapes, bluescreen composites and matte paintings, with visual effects supervisor Bruce Nicholson homing in on the film’s ‘signature’ effect: the floating forcefield bubble created by the two young protagonists.

To create the bubble, the ILM team photographed a plastic sphere under various light conditions – including UV – and manipulated the resulting transparencies on the animation stand. Using holdout mattes, a resized version of the background plate was dropped inside the bubble to create the illusion of refraction. The bubble’s motion was carefully timed to integrate with special effects gags triggered on the live action set, such as collapsing bookshelves and exploding pillows. For a sequence where the bubble rips through the boys’ basement, the ILM crew actually got behind the camera and became a kind of honorary second unit. ‘Joe gave us a real brief storyboard,’ says Nicholson, ‘then just let us go to it … we just tore the place up. We had a great time.’

Among the highlights of the article are the relaxed interviews with make-up maestro Rob Bottin and alien performer Robert Picardo. Between them, the two men paint a vivid picture of life on a soundstage while wearing a full-body suit so heavy that Picardo sometimes had to be ‘moved around the set by means of a forklift.’ According to Picardo, ‘Moving that mountain of rubber … took a lot of energy … If I was moving an inch, you can believe I was acting a mile.’

Dante has nothing but praise for Picardo’s efforts: ‘Bob Picardo is the kind of actor that makes the difference between a well-designed costume and a creature with personality.’ Not for the first time in the annals of Cinefex, we’re reminded of the importance of performance. However well-crafted the creature, without a great performance it’s just a ton of lifeless rubber.

Lifeforce

If Eisenberg’s Explorers article contains hints of the digital shape of things to come, Glenn Campbell’s analysis of Tobe Hooper’s Lifeforce reminds us that, in 1985, photo-chemical processes still carried the lion’s share of the work. Apart from a passing reference to the gruesome animatronics created for the film by Nick Maley, the article focuses wholly on the miniature and optical effects supplied by Apogee under the direction of John Dykstra.

Right from the start, Dykstra set the bar high. To create the diaphanous rivers of light described in the script, he challenged his team to come up with ‘a unique look for an ethereal concept by using laser light.’ After many experiments, they opted to bounce lasers off flexible mylar and capture the resulting spray of colour on a rear projection screen. Special rigs allowed them to manipulate the mylar, curving the spray according to the requirements of the scene. It was painstaking work. Mark Gredell remarks, ‘We worked twelve hours a day and turned out literally thousands of feet [of film],’ though he adds that the laser process was still more cost-effective than traditional animation. He also asserts they achieved Dykstra’s objective: ‘I’ve never seen the same things done before in any other film.’

Right from the start, Dykstra set the bar high. To create the diaphanous rivers of light described in the script, he challenged his team to come up with ‘a unique look for an ethereal concept by using laser light.’ After many experiments, they opted to bounce lasers off flexible mylar and capture the resulting spray of colour on a rear projection screen. Special rigs allowed them to manipulate the mylar, curving the spray according to the requirements of the scene. It was painstaking work. Mark Gredell remarks, ‘We worked twelve hours a day and turned out literally thousands of feet [of film],’ though he adds that the laser process was still more cost-effective than traditional animation. He also asserts they achieved Dykstra’s objective: ‘I’ve never seen the same things done before in any other film.’

If you want a window into the difficult and sweaty reality of photo-chemical opticals, this article is a good place to go. As with Firefox, Apogee were faced with a shiny model that guaranteed unwanted bluescreen spill at every turn. Even their ‘Blue Max’ system (in which narrow-frequency blue light is front-projected on to a Scotchlite screen) struggled to deliver acceptable results. Cameraman John Sullivan describes the eventual solution: a meticulous combination of beauty pass (lit model against black), band-aid matte pass (shadowless, flat-lit model), bluescreen matte pass (unlit model against bluescreen), bluescreen beauty pass (lit model against bluescreen) and sparkle pass (foil-covered model against black).

Frankly, the whole process still astonishes me. Bear in mind that all these passes have to be perfectly repeatable, with both moving camera and miniature following precisely the same trajectories every time to ensure everything lines up in the optical printer. In optical there’s all the massaging of densities and edge characteristics to get everything fitting just right. And I don’t even like to think about the poor guy wrapping the miniature in foil for the final pass that generated the spaceships twinkly aura of ‘captured souls’: ‘Oops, sorry, I bashed the ship with my elbow. Could we just do all that again?’

As if that wasn’t enough, Campbell’s article gives us a second, equally detailed window into another arcane process: rotoscoping. (According to Michael Middleton, Apogee created ‘something in excess of 1800’ articulate mattes for the glowing lifeforce effect as it flowed through the sets, between the open mouths of the characters and so on.)

Back in 1985, rotoscoping meant drawing black shapes by hand on sheets of paper or cel punched with holes to fit an animation camera. Step one was to lace the camera with the production footage you were working with. Using the camera as a projector, you projected the footage on to the bed of the table and traced each frame of animation on to a fresh sheet. After inking, you went back to the stand and used the same camera to shoot your animated mask frame by frame. Deeply laborious stuff.

Middleton talks about all this in some depth, and also gives us the lowdown on the photo-roto process he developed to free up the camera (traditionally you suffer from ‘an inability to shoot and rotoscope at the same time’). Essentially this meant making large blow-ups of each frame on photographic paper which were then taken away and ‘traced to the heart’s content of the animator’. And I do mean large: the paper they used was an unwiedly 24-by-36 inches. It was hard to keep such big sheets of paper flat under the camera, a problem ultimately resolved by installing a vacuum bed under the table.

To my shame, I came back to this particular article thinking I might skim through it. Lifeforce is one of the few films I and my friends nearly walked out of in the theatre (until we realised how unintentionally funny it was) and I had no great desire to revisit it. But I did recall that the opticals were pretty good. I’m glad now that on this re-read I gave Campbell’s text the attention it deserves, because it’s a valuable record of those far-gone photo-chemical days. Great article.

Still a terrible film.

My Science Project

Cinefex #23 closes with Stephen Rebello’s look at My Science Project. Rebello picks up on the tone of that LA Times report with his comment that the summer of 1985 was ‘the summer of the ‘Kids Discover Something Weird genre’. The focus of his article is narrow, concentrating as it does on the creation of a tyrannosaurus rex that ‘cost nearly half a million dollars to realize [and] runs less than three minutes screen time.’

Before getting into that, however, it’s worth mentioning a sub-text concerning Baby: Secret of the Lost Legend, covered back in Cinefex #22 (the full-scale tyrannosaur was built by some of the same Disney crew who worked on Baby‘s brontosaurus family). There are frequent references to Baby‘s ‘mounting effects headaches’ and ‘woes’. Symbolically, the big tyrannosaur was partly constructed using cannibalised brontosaur parts from the earlier movie. And, according to one of the picture captions, ‘as a grim in-joke, chewed-up sections of the Baby miniature were stuffed into the [tyrannosaur’s] blasted stomach.’

Before getting into that, however, it’s worth mentioning a sub-text concerning Baby: Secret of the Lost Legend, covered back in Cinefex #22 (the full-scale tyrannosaur was built by some of the same Disney crew who worked on Baby‘s brontosaurus family). There are frequent references to Baby‘s ‘mounting effects headaches’ and ‘woes’. Symbolically, the big tyrannosaur was partly constructed using cannibalised brontosaur parts from the earlier movie. And, according to one of the picture captions, ‘as a grim in-joke, chewed-up sections of the Baby miniature were stuffed into the [tyrannosaur’s] blasted stomach.’

But the main event is undoubtedly Doug Beswick’s thirty-inch rod puppet tyrannosaur. Rebello romps through acres of detail about the design and construction of this complex creature, which was brought to life by ‘thirty-five cables, five separate joysticks and eight operators.’ The dedication and effort of Beswick’s team shines out of every word. According to Ted Rae, ‘Doug’s mechanisms are like beautiful Swiss clockwork … The work was slow and methodical, but we did things right.’

It’s a shame their painstaking work didn’t really come across on screen. The killer, it seems, was that old enemy: time. ‘We only had four hours off the set for rehearsal time,’ says Tim Lawrence. Compare that to the weeks of rehearsal spent by the puppeteers on Return to Oz (discussed last issue). Sadly, when it came to My Science Project, well-crafted though the dinosaur appears to have been, nobody gave much thought to its performance.

To make matters worse, reshoots meant the opening scenes had to be restaged after later destruction scenes during which the puppet was all but torn apart by ‘BB gun fire and air mortars.’ Tom Hester says, ‘By the end of the first week, the dinosaur was basically hamburger.’ The same thing happened to the baby dragons in Dragonslayer (see Cinefex #6) – yet another reminder that once you take your carefully-built creature on set, it’s just another prop to be torn apart.

The pictures

The Explorers article features the usual excellent spread of images, both behind-the-scenes and frame blow-ups. My favourite shows effects cameraman Don Dow wrangling a mountain of fiberfill clouds into position in front of ILM’s motion control camera. He looks like a man caught in an explosion at a pillow factory.

The Lifeforce article has several choice images showing Apogee’s cutting-edge laser technique in operation, all of which showcase that delightful C-stand-and-gaffer-tape kind of lash-up that typifies the backstage environment of, well, any kind of photographic studio at all.

The photos from the article on My Science Project make Doug Beswick’s dinosaur look pretty darn good, reinforcing my suspicion that its disappointing appearance on screen might have been vastly improved given a little more time and TLC. The side view of the naked armature with all its workings exposed is particularly impressive.

Ten or twenty years earlier, the obvious choice for that tyrannosaur would have been stop-motion. It’s a sign of the times that, by 1985, film-makers had become dissatisfied with that age-old technique. During preproduction on My Science Project, it doesn’t appear to have been on director Jonathan Betuel’s radar at all. ‘The “man in the suit” idea scared me,’ he says, almost certainly referring again to Baby. His inspiration ultimately came from the rancor pit monster from Return of the Jedi (another rod puppet), which he cites as ‘perhaps the best monster for this kind of encounter I’d seen.’

Like Phil Tippett (the man who brought the rancor to life), Doug Beswick had a firm grounding in traditional stop-motion techniques. Moving from stop-motion to rod puppets might not seem like a big step, but it does demand what’s perhaps the single most important quality an effects artist needed in order to survive during the 1980s, when everything was moving so fast (not to mention during the following decade, when new digital techniques sent the rate of change off the scale). It’s the same quality Tippett was famously forced to display in 1993 when Spielberg decided to forego stop-motion dinosaurs for their digital equivalents in a certain film called Jurassic Park.

The ability to evolve.

Did you enjoy this Cinefex retrospective? If so, click here to read the others in the series.

2 thoughts on “Revisiting Cinefex (23): Explorers, Lifeforce, My Science Project”